Hi everyone,

I was itching to do another episode of gmic-adventures, so here it is, and this time we’re going to (finally!) start talking about (small) neural networks!

Introduction

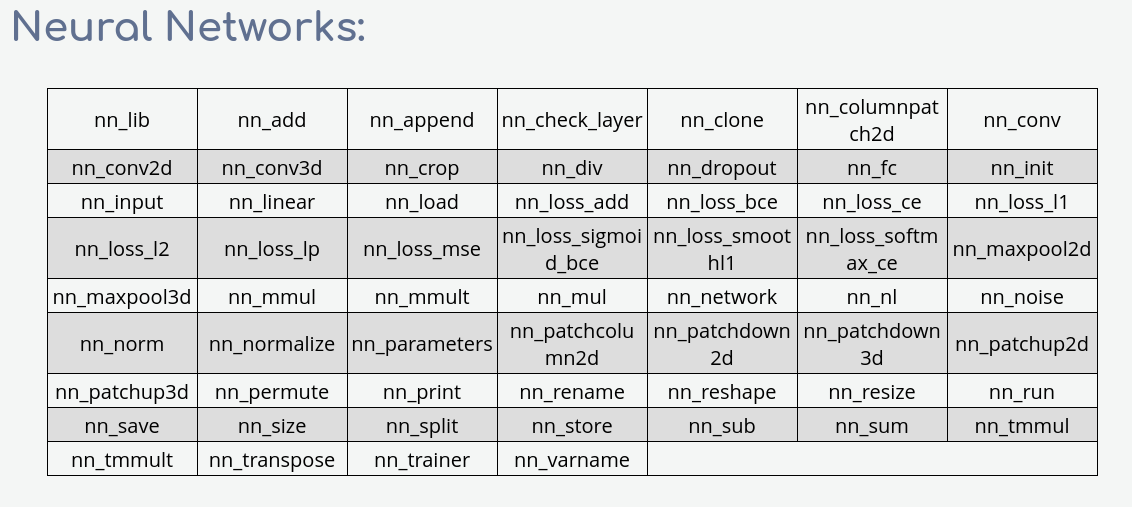

As you know, I have been trying for a few years now to develop a small library (called nn_lib, for “neural-network library”) in order to manage neural networks directly within G’MIC, and I think it’s time to illustrate its use with a simple example.

And what are the simplest neural networks imaginable? MLPs (Multi-Layer Perceptrons), of course! If you are unfamiliar with the concept of MLPs, I suggest you consult the Wikipedia page, which will provide much more information than I could give you here.

But basically, an MLP can be seen as a complex mathematical function that takes a vector IN\in\mathbb{R}^m of any dimension m as input, and outputs also a vector OUT\in\mathbb{R}^n (which may have a different dimension n\neq m).

This MLP function has a certain structure that is basically a sequence of matrix products, additions and non linear functions (activations), all these operations being entirely defined by many parameters (usually several thousand or even millions, for instance used to define the matrix coefficients when doing matrix multiplications). The good thing is that you don’t have to find the parameters by yourself, they will gradually be learned during the training phase of the MLP network, in order to estimate an OUT vector that suits us when we give it a given IN vector as input. And that’s precisely the role of the nn_lib :

- Provide a mechanism and a corresponding API to allow neural network training, such that the network weights are learned iteratively from sets of known (IN,OUT) pairs (which constitutes the so-called training set).

- Once the network is trained,

nn_liballows the user to infer the network : he provides an input IN vector, and the library computes the (expected) network output vector OUT.

Depending on the complexity of the considered network, the required size of the training set can be very large, meaning the training can take age (I mean millions of iterations). But for our episode here, I will limit myself to a quite simple MLP network, so the training time will remain acceptable, even with the nn_lib (that only takes advantage of CPU cores).

Objectives

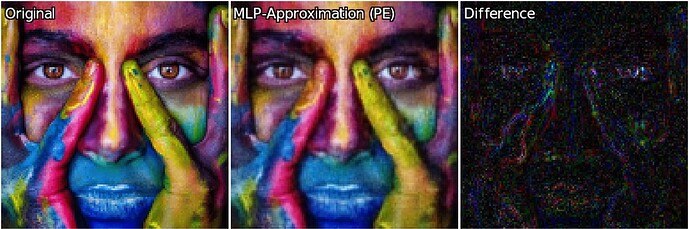

In this episode, my goal is then to show you how to use the nn_lib to quickly design and train a small MLP that takes an input IN\in\mathbb{R}^2 (that represents a coordinate vector (X,Y) ), and estimate an output OUT\in\mathbb{R}^3 (that represents a (R,G,B) color). Thus, we’ll design a network that is intended to learn a complex multi-valued function (X,Y) \rightarrow (R,G,B), from scratch (so basically, a color image!).

I’ll show you how this can be done as a G’MIC script (less than 50 lines of code), and show you then some variations afterwards, for a quick, fun, little trip into the magic world of neural networks.

Important note: We won’t talk about generative AI here, as the kind of networks involved for generative AI are much much larger and complex than the one illustrated here. Neural network is the (current) basis under all the “AI” trend (how much I dislike this term!). And while the use of general AIs may be open to criticism (for many reasons), understanding how neural network algorithms work is really fun and interesting!

Also it’s winter, so make the most of it—with nn_lib, your CPUs will quickly heat up the room!

Spoiler

This is a typical result of what our neural network learning algorithm will generate after a few lines of code. In the video below, you can see successive training iterations of a basic MLP, trying to learn one complex function (X,Y) → (R,G,B) (which is here the image produced by the G’MIC command sample colorful).

Stay tuned! ![]()